The first celebrity gardener, half a century before Alan Titchmarsh or Monty Don, was Mr Middleton. His wartime radio show popularised ‘Dig for Victory’, launching suburbia’s enduring love affair with the allotment. Few of the 3.5 million Home Service listeners knew he even had a first name, but Cecil Henry Middleton’s homespun advice and amiable

The first celebrity gardener, half a century before Alan Titchmarsh or Monty Don, was Mr Middleton. His wartime radio show popularised ‘Dig for Victory’, launching suburbia’s enduring love affair with the allotment.

Few of the 3.5 million Home Service listeners knew he even had a first name, but Cecil Henry Middleton’s homespun advice and amiable tone made him the perfect choice to guide the back-garden growers keeping 1940s Britain in carrots and spuds.

Born on February 22 1886 in the village of Weston, Northants, the love of gardening came from his nurseryman dad John. By 17 he was in London, working first for a seed firm, then at Kew Gardens. At the outbreak of the First World War (and by then married to Rosa Jenkins) he landed a job at the Board of Agriculture before becoming Surrey County Council’s horticulture instructor. The allotment council he set up named its top competition prize after him.

Cecil and Rosa were the first occupants of 17 Princes Avenue, round the corner from Tolworth Broadway, moving in the moment the semi was finished in 1927.

Needing someone to front a radio show, the BBC asked the Royal Horticultural Society for ideas. The first try-outs sounded stiff and patronising… but not our Cecil.

His reflective, matter-of-fact delivery (and the odd dropped aitch) hit the mark. He made his debut on May 9 1931 with a 15-minute talk, The Week in the Garden. “Good afternoon. Well, it’s not much of a day for gardening, is it?” he began, setting the self-deprecating tone. Until then, radio had used the likes of Vita Sackville-West to formally describe stately home gardens, rather than offer listeners practical tips.

Armed only with scribbled notes, Mr Middleton spoke to the nation, addressing his listeners as equals. At his peak he achieved the highest audience figures in broadcasting history.

Middleton had the gift of simplification – a prototype of the character Chauncey Gardiner from the Peter Sellers film Being There. Yet his 12 guinea fee per show wasn’t paid into his Surbiton bank account, but to the council! No wonder he left to take a £1,000-a-year job with the Sunday Express.

In 1937, from a specially created plot at Alexandra Palace, he made television’s first gardening outside broadcast, at a time when there were only 2,000 sets in the UK!

TV halted in wartime (Middleton was never on the box again), but his radio show was essential listening. To counter food shortages, he spearheaded Dig for Victory, achieving an incredible scale of planting. Parks were dug up, roundabouts sown, and food worth £20m a year was grown – the equivalent of £4.2bn today.

The critics loved him. Wilfrid Ley said he “assumes your soil is poor and your pocket poorer” and that “all he asks is that your hopes are high and your Saturday afternoons are at his service”.

During the Blitz, Mr Middleton (who wore a suit and tie, even when digging) did a reading at a special service in St Martin-in-the-Fields, to bless allotments.

In his Express column, he wrote that “we can turn our gardens into munitions factories, for potatoes and other vegetables are munitions of war as surely as shells and bullets”. He advised: “Do not think of your allotment as an ordeal or a wartime sacrifice. Regard it as your pleasant and profitable recreation.”

Yet for all the veg talk, he adored flowers. A colleague said he found vegetables “dull”, adding: “He couldn’t love an onion where a dahlia might grow.” His own garden disappointed. Neighbours in Tolworth were amused that the man who lectured to the nation had bland plots, front and rear!

“Turn to the right of the Kingston By-Pass when you get to the Ace of Spades corner, and soon you will come to a quiet retreat of London suburbia known to the postman as Princes Avenue,” one obituary would read. “Its gardens are kempt and gay… but the least kempt and gay of them all is No17, the house of the greatest and most famous gardener England of this century has known. Our Mr Middleton never had enough time for his own small plot, which measured 50 yards!”

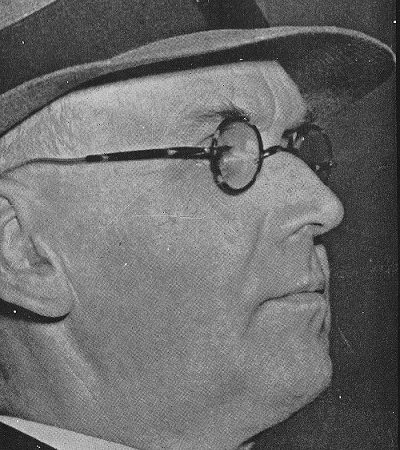

Bespectacled and receding, Middleton wielded power. A word on his weekend radio show would lead to mass buying on Monday mornings from seedsmen and sundriesmen – the garden centres of their day.

Ever understated, he rivalled Winston Churchill for bon mots. “Sow, grow, hoe, show, crow!” “How we should miss the poor old humble cabbage if we didn’t have it.” “There’s no substitute for digging, or if there is I haven’t found it.” “An allotment is like the army; the first month is the worst, after that you begin to enjoy it.” In the darkest days of war he said: “The harder we dig for victory, the sooner roses will be with us.” But he also suggested “taking a day off from Hitlerism” to enjoy the summer.

The War Office didn’t always approve. He got into trouble when, commenting on a lime shortage, he told listeners not to worry as “the way things are going at the moment there will soon be plenty of mortar rubble about”. He was right. In autumn 1940 his Tolworth home was partly destroyed by a German bomb, and he had to move in with relatives until February 1942, when his semi was rebuilt.

Books became a further source of income. His 1941 bestseller was Mr Middleton’s Garden Book, a vast 1,024-page tome. Quite what fellow Princes Avenue residents made of its forthright advice isn’t known. “Having trouble with a neighbour?” Middleton wrote. “Hit him over the head with a spade!”

The following year, Digging for Victory, a wartime gardening book, became a self-sufficiency bible with instructions on what to plant and when to harvest.

After VE Day in May 1945, Mr Middleton urged his new army of garden converts to continue their efforts. “We may have to change Dig for Victory to Dig for Dear Life,” he said, as food continued to be rationed in post-war Britain. “Whatever we call it, we must not slack our efforts; the need for intense food production is more urgent than ever.”

Four months later, Mr Middleton was dead; suffering a fatal heart attack as he closed his garden gate in Princes Avenue.

His last journey was from St Matthew’s church; the hearse and limousines decked out with autumn flowers which had been sent by listeners from their suburban gardens across the land.

Mr Middleton died five months short of his 60th birthday, but his widow, Rosa, lived on – alone – in the house in Princes Avenue well into her 80s.

Cecil Henry Middleton, born February 22 1886, died September 18 1945

1 Comment

Pete Seward

8th May 2020, 3:38 pmI delivered papers to that house in the mid 60s

REPLY