The man who gave a new meaning to needlework by transporting an ancient Egyptian obelisk to London was a Surbiton engineer. Shifting a 69ft red granite monument 3,000 miles and installing it on the Embankment looked impossible in the 1870s, but John Dixon relished a challenge. The hieroglyph column, made in around 1450 BC and

The man who gave a new meaning to needlework by transporting an ancient Egyptian obelisk to London was a Surbiton engineer.

Shifting a 69ft red granite monument 3,000 miles and installing it on the Embankment looked impossible in the 1870s, but John Dixon relished a challenge. The hieroglyph column, made in around 1450 BC and weighing 224 tons, fell into what eBay would today call the ‘buyer collects’ category.

It had been given to Britain in 1819 by the Egyptian ruler as a thank-you for Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, but the UK government had blanched at the cost of transporting it home.

So the well-meant but hopelessly impractical gift sat in Alexandria. Seventy years passed, and the site owner was threatening to break it up for building stone.

A private philanthropist agreed to stump up £10,000 to bring the column to London, so Dixon, then in his early 30s and living in Portsmouth Road, right, set to work.

Overland transport was too costly, so he hatched a plan with his brother Waynman to encase it in an iron cylinder and tow it to Blighty by steamship.

The only precedent had been the obelisk in Place de la Concorde, Paris, which had been moved from Egypt in 1836 in a specially built ship.

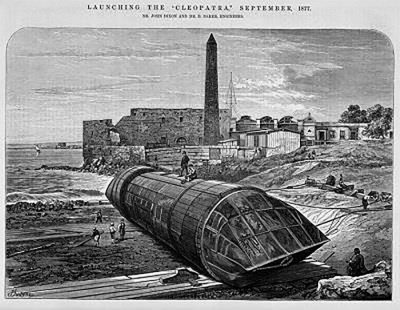

John Dixon’s towing tube was shipped to Alexandria in bits, reassembled, and the obelisk manoeuvred in. The journey was going well until, in October 1877, a storm in the Bay of Biscay caused the cylinder (nicknamed Cleopatra, pictured below in the Illustrated London News) to roll over and disappear from view.

A rescue boat from the steamship Olga was dispatched, but capsized with the loss of all six crew. The obelisk was presumed to have gone to the bottom of the sea, but was later found bobbing after the storm abated. It finally arrived by tug at East India Docks, was unpacked and hauled to the Embankment when it was formally unveiled in September 1878. London’s governing body paid for two stone sphinxes to complete the look, although haste (and misunderstood instructions) meant that they were unfortunately placed staring at the column, and not gazing outwards.

A rescue boat from the steamship Olga was dispatched, but capsized with the loss of all six crew. The obelisk was presumed to have gone to the bottom of the sea, but was later found bobbing after the storm abated. It finally arrived by tug at East India Docks, was unpacked and hauled to the Embankment when it was formally unveiled in September 1878. London’s governing body paid for two stone sphinxes to complete the look, although haste (and misunderstood instructions) meant that they were unfortunately placed staring at the column, and not gazing outwards.

Shocked and upset by the deaths of the steamship crewmen, Dixon set up a fund to support their families.

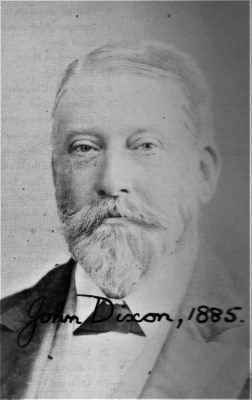

Dixon was born in Durham in 1835, the eldest of three brothers and three sisters. He left school at 14 and was apprenticed to Robert Stephenson, the top engineer of the 19th century and creator of The Rocket.

Dixon became manager of an ironworks before deciding fame and fortune lay in London. In 1862 he had married Mary England, pictured below, herself the daughter of an ironworks owner. He was 27, she 20.

Five years later came the move to Surbiton, initially to 13 St Philip’s Road, where, from the upper windows, John and Mary (and the three children they had then produced) could watch boats on the river, with no homes in North Road or Maple Road to block their view. The family kept growing. There would eventually be 11 children, with two sons and seven daughters surviving to adulthood.

Five years later came the move to Surbiton, initially to 13 St Philip’s Road, where, from the upper windows, John and Mary (and the three children they had then produced) could watch boats on the river, with no homes in North Road or Maple Road to block their view. The family kept growing. There would eventually be 11 children, with two sons and seven daughters surviving to adulthood.

So in 1875 they moved to a bigger home, The Choubra (named after a fashionable district of Cairo) at 28 Portsmouth Road, by the Anglesea Road junction, where Surbiton and Kingston meet.

Dixon soon embarked on one of the strangest projects in local history. Seven years earlier, he’d taken out a patent on a ‘floating saloon bath’. Basically, it was a fenced-off section of river or sea which could be safely used by swimmers.

It allowed the free flow of water through filters at each side, it was supported by floating pontoons, and it had changing rooms and a viewing gallery at water level.

In 1875 one opened on London’s Embankment – near the spot the needle would later occupy. Bathers paid a shilling a time (5p), according to research by biographer Ian Pearce (John Dixon: The Man Who Could Have Built the Forth Bridge, Tyne Bridge, 2019).

The Dixons’ home in St Philip’s Road, Surbiton

Dixon proposed a similar one for Surbiton and Kingston residents at the High Street end of Queens Promenade… and instantly ran into strong opposition from Thames Sailing Club, which had been formed five years earlier and wanted no structure interfering with its yachts.

Dixon prevailed. Kingston Council backed his idea, to give the crowds that filled the prom on warm days something new to do in summer. His floating bathing area was not intended, he insisted, “for the great unwashed of Kingston and the small unwashed of Surbiton”, but for recreational use!

At a cost of £1,500 the floating bath was built out of wood, 150ft long and 40ft wide, and supported on pontoons. It was moored at Town End Wharf, where Kingston High Street meets Portsmouth Road, opposite the point where The Anglers block (pictured below) currently sits.

Opened with much fanfare in 1882, its hours were 6am to dusk, May-September. Fee for bathing: tuppence.

But Thames Conservancy immediately ordered its removal and, on August 11 1882, sent a tug to haul the floating bath away.

In an extraordinary stand-off, bigwigs from Kingston Council started grappling with the Thames Conservancy officials as the steam tug’s crew tried to cut loose the bath’s anchor chains. Alderman Gould sustained a leg injury from a boathook.

Mr Payne from Thames Conservancy shouted: “I’ll remove that bath piece by piece if necessary.” This was solemnly recorded by the Surrey Comet reporter in his notebook, but Mr Payne snatched the notebook away, tore it up and threw the pieces in the river.

Mr Payne from Thames Conservancy shouted: “I’ll remove that bath piece by piece if necessary.” This was solemnly recorded by the Surrey Comet reporter in his notebook, but Mr Payne snatched the notebook away, tore it up and threw the pieces in the river.

Supt Digby of the local police force, who had been observing events, decided it was time to intervene. He broke up the fracas, Thames Conservancy’s tug withdrew and the council won the day. Through the summer of 1882 200 people used the bathing pool each day; mostly ‘lads’.

But the following year Kingston’s mayor, Cllr James Thrupp Nightingale, ordered an inquiry. The floating bath had weathered badly over winter, and was no longer fit for use. Dixon and the council haggled over who was responsible for repairs, with the local authority deeming Dixon’s manner ‘discourteous’, and adding: “He treats the corporation in a contemptuous way, as nobodies.”

The Dixons had wearied of the floating bath saga. In 1884 they left Surbiton and moved (with their cook and three maids) to Selborne Road, Croydon – an area they’d got to know from visiting several sets of friends.

Queens Prom’s famous floating bath was broken up, and the concept of river pools fell out of fashion and transferred to dry land with the opening, half a century later, of the Coronation Baths in Kingston and Surbiton Lagoon.

Does a photograph, or even a sketch, of John Dixon’s 1882 floating bath exist? One has yet to come to light, and unfortunately local snapper Eadweard Muybridge was busy working in the USA at the time.

Dixon’s CV sums up the world reach of British engineering in the 19th century: drainage projects in Brazil; piers in the Isle of Man, Llandudno and Southport; wharves in Spain; landing stages in the UK and Portugal; a bridge over the Nile in Cairo; a harbour in Wales…

In 1875 he won the concession for the first railway in China, in suburban Shanghai – a project plagued with difficulty as locals kept lifting the freshly laid tracks for fear they would upset the spirits of their ancestors.

In 1875 he won the concession for the first railway in China, in suburban Shanghai – a project plagued with difficulty as locals kept lifting the freshly laid tracks for fear they would upset the spirits of their ancestors.

Then, using his geological skills, he located a previously unknown source of fresh water on the Rock of Gibraltar, so locals no longer had to import supplies from the mainland.

Dixon also rebuilt Hammersmith suspension bridge between 1884 and 1887.

A staunch Tory, and active member of the committee of Kingston Conservative Association, he was briefly a freemason, although he rapidly lost interest in it and gave up his lodge membership after less than a year.

Articulate, eloquent and a gifted watercolour artist in his spare time, Dixon’s contribution to engineering was immense. Recognising this, the press agitated for a knighthood, but our Notable Surbitonian had to settle with being made a CBE.

In 1891, John Dixon developed heart problems. He died at his Croydon home, aged 56. His numerous projects had made him a wealthy man. His estate was valued at more than £11,000 (over £1m today). Mary died in 1907 at the age of 65.

John Dixon, born in Durham, January 2 1835, died in Croydon, January 28 1891

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *